The Blasket Islands: History and Heritage

This article and its accompanying photographs are taken from the booklet "Na Blascaodaí / The Blaskets", written by Pádraig Ua Maoileoin, who was born in Dunquin in 1913 and died in 2002. He was known for his work in Irish lexicography and his poetry and novels won him several awards, including the Oireachtas prize in 1982 for his novel "Ó Thuaidh!" The copyright is held by the Government of Ireland and the material is used with the permission of Ionad an Bhlascaoid Mhóir / The Blasket Centre, Dún Chaoin, Co. Chiarraí.

THE NAME / Ainm

The Blaskets are and have always been an intrinsic part of the parish of Dún Chaoin. Even the most casual of observers will notice that the Islands and mainland were once one, perhaps a few million years ago; the experts confirm this impression.

Locally, the Great Blasket was called simply the Island, or more formally, the Western (or Great) Island. The Blasket Islanders themselves referred to the other Islands as the Lesser Blaskets. In the past the whole group of Islands was referred to as Ferriter's Islands. From the end of the 13th Century the Ferriter family leased the Islands from the Earls of Desmond, and from Sir Richard Boyle after the dispossession of the Desmond Geraldines at the end of the 16th Century. They retained a castle there, at Rinn an Chaisleáin (Castle Point) in the lower village. There are no physical remains of that castle because the stones were carried off to build the Protestant soup-school in 1840. The same school was closed down in 1852 after the ravages of the Great Famine.

The last of the Ferriters to control the Blaskets was the poet and rebel chieftain, Captain Piaras Feirtéar. He was hanged at Cnocán na gCaorach in Killarney in 1653, after he and his followers were defeated at Ross Castle nearby. The word "Blasket" itself is a mystery. No one knows when or who first gave it that name. In the 14th and 15th Centuries the names "brasch", "brascher" and "blaset" are recorded on contemporary Italian maps; in 1589 a variant form of these names, "Blasket Isles", appears for the first time. Blascaod/Blasket has all the characteristics and resonances of a foreign borrowing. Robin Flower has suggested that it originates from the Norse word "brasker", meaning "a dangerous place."

FLORA & FAUNA / Míolra agus Fásra

The Great Blasket is coated on top with a covering of furze, whins and heather, with peat (or bog or turf) beneath much of it. Turf, at a depth of one sod below the stripped surface, was usually cut with a spade.

The soil around the village is sandy, about 60 acres of it arable land; a little valley or cleft runs through the village to the sea, and ivy, holly and goat willow grow there, twisted and weathered by storms. Osiers fit for basketmaking do not grow there, and as a consequence the Islanders had to travel to the mainland, sometimes as far east as Abhainn an Scáil (Annascaul) and Ínse (Inch), to get a supply in season for making their lobster pots.

The Blasket is, and always was, teeming with rabbits. Yet it is a miracle of sorts that none of the following species is recorded on the Island: the weasel, frog, or hare; neither was the fox or the rat, the hedgehog, badger or newt. The long-tailed field mouse and the pygmy shrew were the commonest of all species on the Island.

BIRDS / Èanlaith

Seabirds which never frequented the coast of the mainland were abundant there, and they are still to be found, though not in such numbers since their food supply decreased. These include the storm petrel (breeding in thousands in the island wilderness), guillemots, puffins, razorbills, the Manx shearwater, and the black guillemot. Their fledglings provided many a juicy mouthful for the Islanders when hunger stalked the countryside. Together with the nestlings of the gannet from the Sceilg, these kept the hunger from the door.

THE PEOPLE / Na Daoine

According to Charles Smith, author of "The Ancient and the Present State of the County of Kerry (1756)", the Great Blasket was uninhabited prior to about 1710, except for monks in ancient times. A recently-discovered document, however, records people living there in 1597. (A ship's captain left the document which was found in an archive in Samancas, Spain. He calls the Islands "Yslas de Blasques" and would have us believe that the inhabitants were all fluent Spanish speakers!) The very fact that the Ferriters controlled these Islands as far back as the 13th Century, and maintained their own castle there, is a clear indication that they were inhabited at an early stage.

According to Charles Smith, author of "The Ancient and the Present State of the County of Kerry (1756)", the Great Blasket was uninhabited prior to about 1710, except for monks in ancient times. A recently-discovered document, however, records people living there in 1597. (A ship's captain left the document which was found in an archive in Samancas, Spain. He calls the Islands "Yslas de Blasques" and would have us believe that the inhabitants were all fluent Spanish speakers!) The very fact that the Ferriters controlled these Islands as far back as the 13th Century, and maintained their own castle there, is a clear indication that they were inhabited at an early stage.

According to popular tradition, the first people to live on the Blaskets herded animals, grew crops and hunted. That folk memory must extend a long way back, because the seine boat changed their way of life completely when it made its appearance for the first time on the Blaskets at the beginning of the 19th Century or shortly before. Until then they fished only from the rocks with hand lines. The seine boat gave them the means to take to fishing as a way of life, and they gave up tillage almost completely apart from potatoes, a little oats and some vegetables.

POPULATION / Lion na nDaoine

The number of people living on the Island has ebbed and flowed. There was a population of about 150 living there in 1840, but after the Great Famine that had decreased to 100. The population is said to have reached its peak in 1916, at 176. From then on it was in decline until 1953/54 when the Blasket was abandoned.

The number of people living on the Island has ebbed and flowed. There was a population of about 150 living there in 1840, but after the Great Famine that had decreased to 100. The population is said to have reached its peak in 1916, at 176. From then on it was in decline until 1953/54 when the Blasket was abandoned.

The population of the Island grew with the influx of tenants evicted from their holdings by Lord Ventry during the first half of the 19th Century. It is certain that the Criomhthain and Duinnshléibhe families from Márthainn and Baile na Rátha on the mainland settled on the Blasket during that period. Many others followed the same path, because the way of life there was better than what they had to endure on the mainland. Nevertheless, Island life was a constant hardship and struggle – a three-mile crossing to the mainland, followed by a five-mile walk by road for a priest, or a twelve-mile walk to reach a doctor.

THE WAY OF LIFE / Mar a Mhaireadar

The Islanders survived mainly on fishing, a few ridges of potatoes, and a patch of oats or rye. Some of them had a cow or two; others who had none would depend on a drop of milk from the neighbour who had. The land was poor and sandy around the houses and their own plots were scattered here and there. A year's supply of manure would not go far on the smallest of holdings, and the dung had to be supplemented by material from the beach – mussel shells and seaweed; sometimes even the soot from the chimney was spread as fertilizer. Seaweed was plentiful on their own shores but they had to cross over to nearby Beiginis to gather mussels.

The Islanders survived mainly on fishing, a few ridges of potatoes, and a patch of oats or rye. Some of them had a cow or two; others who had none would depend on a drop of milk from the neighbour who had. The land was poor and sandy around the houses and their own plots were scattered here and there. A year's supply of manure would not go far on the smallest of holdings, and the dung had to be supplemented by material from the beach – mussel shells and seaweed; sometimes even the soot from the chimney was spread as fertilizer. Seaweed was plentiful on their own shores but they had to cross over to nearby Beiginis to gather mussels.

The mountain was held in common by all the Islanders, with turbary rights and a right to hunt rabbits. There was an unwritten rule in force regarding the grazing of sheep: 25 sheep for each grazing cow, and the man who did not have a cow was not allowed to graze sheep on the mountain. Nobody now remembers pigs being reared on the Island, although there were pigs kept during the 19th Century. Nobody remembers any horses there either; but it appears they once did have horses drawing wooden ploughs.

Donkeys – males only – took the place of the horse; they had no use for females because the land was so steep and precipitous that they would have driven each other over the cliff when in season. The donkey carried turf in panniers from the mountain, and sand and seaweed from the strand. The donkey was never harnessed for ploughing on the Island.

TILLAGE / Curadóireacht

The years 1878-79 witnessed successive failures of the potato crop; blight destroyed the Islanders' crop as effectively as it did on the mainland, and in 1879 the Government of the day, having learned the lessons of the Great Famine, helped relieve the situation by providing yellow meal to those in need. That year became known on the Island as the Year of the Free Cornmeal.

Shortly afterwards they got another gift from God in the guise of the Champion seed potato. At the time, the Earl of Cork was the landlord of the Islands (and much of the mainland as well) until the Congested Districts Board purchased them in 1907. The Earl supplied Champion and Black seed potatoes free to all his tenants in 1880.

Potatoes were planted in ridges. Each sod was turned and each furrow dug with the spade. It was backbreaking work, though the ground itself crumbled easily beneath the spade. From St. Brigid's Day (the 1st of February) onwards, the cutting edge of the spade would be sharpened in preparation.

From 1905, when visitors began regularly to stay on the Island, some extra vegetables – carrots, onions, lettuce, turnips and the like – were grown by the households in which they lodged.

FISHING / Iascach

The early inhabitants of the Island were not fishermen. Fish was in great abundance at that time, however, and they satisfied their needs with fish caught on hand lines from the rocks. With the introduction of the seine boat they were able to undertake fishing as a livelihood. Horse-mackerel was their main catch until the 1870s when it was displaced by pilchard. Then came their great sea harvest, the big Spring mackerel.

The early inhabitants of the Island were not fishermen. Fish was in great abundance at that time, however, and they satisfied their needs with fish caught on hand lines from the rocks. With the introduction of the seine boat they were able to undertake fishing as a livelihood. Horse-mackerel was their main catch until the 1870s when it was displaced by pilchard. Then came their great sea harvest, the big Spring mackerel.

Around that time the changeover occurred from the seine boat to the "naomhóg", or canoe. In "An tOileánach" – "The Islandman" – Tomás Ó Criomhthain states that the first naomhóg was brought to the Island by two Islanders who purchased it while under the influence of drink in Dingle!

Around that time the changeover occurred from the seine boat to the "naomhóg", or canoe. In "An tOileánach" – "The Islandman" – Tomás Ó Criomhthain states that the first naomhóg was brought to the Island by two Islanders who purchased it while under the influence of drink in Dingle!

The naomhóg was an easier craft to handle and to manoeuvre than the seine-boat. A three-man crew could manage it at their ease whereas the seine boat took a crew of eight and also required a back-up boat, called a "foilár", perhaps from the English "follower". It was a cumbersome, awkward craft to beach. The naomhóg was much handier and more manageable in many ways. It could take a sail when the wind was right; it was easier to turn and manoeuvre; and, when needed, it could be taken closer to the rocks. It also widened the range of work and variety of catches. Henceforth, they could trawl their lines, set trammel-nets and troll for pollock. The naomhóg's only major drawback was that it was difficult to transport an animal in it.

They caught all their large coarse fish with trawl lines – ling, halibut, cod, large halibut, eel, dog-fish, etc. Wrasse, red sea bream, and the like were fished with trammel-nets.

A CHANGE IN THE WAY OF LIFE / Athrú Saoil

Another major change in their way of life at this time was the discovery that other species of fish never before fished by the Islanders – lobsters and crayfish – were also of value. They were absolutely bemused when they saw a naomhóg from Dingle fishing lobster and crayfish with pots near the Island. They quickly learned how it was done, and were shown how to make the pots by two Englishmen – Parsons and Nicholson, who were fishing lobster and crayfish with fishermen from the Iveragh Peninsula. Before long the Islanders were as skilled as any at lobster fishing.

For many years Dingle was the only market for their lobster. That was until the Frenchman Pierre Trehiou came to the area with his large storage ship in the 1920s. He bought the lobster directly from the Islanders. The French vessel had a huge storage tank midship with an iron-mesh net at the bottom, leaving it open to the sea; hundreds of lobsters swam in the tank snapping at one another and feeding from the strips of hanging bacon.

The Frenchman and the Islanders got on very well together, and as their relationship grew the Islanders learned to count in French, as well as learning a few French phrases. They had an agreement to exchange goods and got nets, tobacco, wine, rum, or anything else they needed on credit; those items to be debited to their account against the next haul of lobsters.

But the big change came with the early 1930s. The Island community began to decline and the young people were loath to marry. Only two couples married there between then and the time of its abandonment, with most making off for America where so many of their kin had preceded them. In some cases entire households left in the 1940s and settled on the mainland. Their courage had deserted them a long time before the year of the great exodus in 1953; they felt the boat sinking under them.

HOUSES / Tithe

The maximum number of houses on the Island, at its peak, was 30. In 1909 the Congested Districts Board built five two-storey houses at the top of the village, looking down on the rest of the houses, but totally out of character with them. The older houses faced either north or south (except for one of later vintage) with the uppermost gable (the hearth wall) bedded into the hillside for shelter.

The maximum number of houses on the Island, at its peak, was 30. In 1909 the Congested Districts Board built five two-storey houses at the top of the village, looking down on the rest of the houses, but totally out of character with them. The older houses faced either north or south (except for one of later vintage) with the uppermost gable (the hearth wall) bedded into the hillside for shelter.

All the houses had a large kitchen, with enough room to dance a set or to wake a corpse, an adjoining "lower room", and in some cases an "upper room" behind the hearth wall. The kitchen had to be large enough to accommodate animals at night or during bad weather. There was a loft above the lower room – in some houses a makeshift bed was placed there – and a narrow loft above the fire for storing nets, fishing lines, trawl lines and other goods.

The houses on the Island usually had one door only, unlike mainland houses which had two doors at the front and back, one kept open and the other closed. Tomás Ó Criomhthain's house was the exception in this case; he built the house himself, in imitation of the mainland style presumably. Some writers have stated that the Island houses were once thatched with straw. This cannot be so, for they rarely had sufficient straw; and long, strong straw is necessary for thatching a roof. In the 19th Century the houses were usually roofed with rushes. The naomhóg, which has a tarred felt covering, gave them another idea. Felt was an ideal roofing material and in most cases it replaced the rush thatch in both houses and outhouses. (The five two-storey houses built by the Congested Districts Board had slate roofs, and Peig Sayers lived in one of these.) The walls were built of stone and mortar, with earth floors inside; a couple of flat flagstones in front of the fire comprised the fireplace. The earth floors were constantly damp and to keep them dry they spread sand from the beach on them a couple of times a day.

The houses on the Island usually had one door only, unlike mainland houses which had two doors at the front and back, one kept open and the other closed. Tomás Ó Criomhthain's house was the exception in this case; he built the house himself, in imitation of the mainland style presumably. Some writers have stated that the Island houses were once thatched with straw. This cannot be so, for they rarely had sufficient straw; and long, strong straw is necessary for thatching a roof. In the 19th Century the houses were usually roofed with rushes. The naomhóg, which has a tarred felt covering, gave them another idea. Felt was an ideal roofing material and in most cases it replaced the rush thatch in both houses and outhouses. (The five two-storey houses built by the Congested Districts Board had slate roofs, and Peig Sayers lived in one of these.) The walls were built of stone and mortar, with earth floors inside; a couple of flat flagstones in front of the fire comprised the fireplace. The earth floors were constantly damp and to keep them dry they spread sand from the beach on them a couple of times a day.

The Islanders had their own methods for smoking and home-curing food; they hung cured fish above the mantelpiece to dry, and bacon which was smoked.

FURNITURE / Troscáin

Simple and basic are the two words which best describe their house furnishings. A wooden bed or two with side-rails; in some houses an iron bed as well, perhaps; a press or trunk, brought from America or thrown up by the sea, stood between the beds and was used for storing bedding or other clothes; and finally, a chamber-pot was strategically positioned between the two beds! Blankets were made from their own sheep's wool, and a handmade patchwork quilt on top of those; sheets were made from flour sacks, and underneath mattresses stuffed with goose down that were so comfortable you would sink into them up to your oxters.

A dresser on one side and a cupboard on the other made a partition between the lower room and the kitchen, with an opening between both as a door. A strong sturdy table, and in former times a small table or kneading-trough, as well as sugawn (straw rope) chairs – all these they made themselves, often with driftwood. A wooden couch stood against the sidewall, and items such as sheep shears, shoes and blackening were stored underneath; and a hen coop, perhaps, below that again. In some houses a settle-bed took the place of the couch which, when opened out, would make a bed at night for two or three persons.

A dresser on one side and a cupboard on the other made a partition between the lower room and the kitchen, with an opening between both as a door. A strong sturdy table, and in former times a small table or kneading-trough, as well as sugawn (straw rope) chairs – all these they made themselves, often with driftwood. A wooden couch stood against the sidewall, and items such as sheep shears, shoes and blackening were stored underneath; and a hen coop, perhaps, below that again. In some houses a settle-bed took the place of the couch which, when opened out, would make a bed at night for two or three persons.

The first pot-oven brought onto the Island was that used by the "soup school" at the time of the Great Famine. Island writers record that before long three pot-ovens were in use, and finally every house had one. All of their baking and roasting was done in the pot-oven. Besides the pot-oven, each house had an iron pot and skillet in which food was boiled – potatoes, fish and meat – and clothes soaked before washing.

FOOD & SUSTENANCE /Bia agus Beatha

When the potato failed during the Famine, the Islanders suffered as badly as any community on the mainland. Unlike most mainland communities, however, they depended less on the land for sustenance and managed better. As a consequence, some mainland families fled to the Island at this time and settled there.

There was no shop on the Island. They had therefore to go to the mainland for flour and any other household goods. Bread, home-baked of course, gradually replaced the potato as the mainstay of their diet. The owner of a cow had a source of butter, as well as buttermilk on churning day. Hand-churning was the method used for making butter. They are unlikely ever to have used a churn since they did not produce cream in sufficient quantities to warrant its use. They drank skimmed milk – apart from the jug of fresh milk kept aside for tea purposes. Thick sour milk was a favourite drink, or a mixture of milk and water to slake the thirst on a fine day while working in the field.

SHEEP / Caoirigh

There was a saying on the Island about sheep: "a sheep to sell, a sheep to shear, and a sheep to eat." Sheep were an important indicator of a man's wealth. Twice a year each household killed a sheep and cured a portion of it. The women were experts at stuffing some of the sheeps' intestines.

The Blasket sheep had a great reputation for their flavour and Dingle women would invariably ask their butcher if he had Blasket mutton. No doubt some butchers would falsely claim that the mutton they had for sale originated on the Blaskets!

MEALS / Béilí

In the 19th Century the Islanders ate two meals a day, morning and evening. Both meals consisted of potatoes and fish, with a bowl of sour milk if you were lucky. The advent of tea affected their eating habits. It was first washed ashore in a sturdy tea-chest (not the only chest of tea that fortune sent their way) and, as Tomás Ó Criomhthain writes, they did not know what to do with it. Eventually someone drank it, and that was that. A new era had dawned and soon the whole Island was drinking tea. Now it was tea and bread in the morning and again late in the afternoon; potatoes at midday and again at night. Until 1953 when the Island was abandoned they had four meals a day.

FISH / Iasc

They preferred to boil all fish, except for mackeral and breem which were usually roasted on the tongs. There was no mention of salmon, or demand for it, at that stage, and they did not value it. It was usually thrown back into the sea or cut up for lobster bait! They had a great liking for roasted seal meat because of its richness – many preferred it to pork.

They preserved the sealskin and used it as a floor mat. Oil was extracted from the liver of the seal, and this was used widely for healing wounds and other injuries.

DELICACIES / Sólaistí

Shellfish, such as limpets and periwinkles, were another great favourite. Dulse, sea lettuce and pepper dulse, and certain other varieties of seaweed – especially sea belt and murlins – were eaten. If they were hungry enough they would eat the limpets and periwinkles raw. They were not very fond of lobster as food, but they would eat the lobster roe from their fists while fishing. Crab was the most prized of all, especially the red crab, not boiled but roasted in hot ashes. Some hardy individuals would eat raw crab straight from the sea.

One of the favourite delicacies was a mountain rabbit caught with a snare or hunted with ferrets; other favourites were seabirds – the storm petrel, the puffin, the razorbill or the young of the gannets from the Skeiligs – all roasted in the pot-oven or on the tongs in the heart of the fire. Gull's eggs were eaten in season as well.

DRINK / Deoch

As regards drink, they had to rely for most of their lives on clear cool water. They had little experience of alcoholic drink apart from what little the Frenchman would give them in part-exchange for their lobster and crayfish, or the infrequent barrel of wine and spirits washed ashore from the sea. Otherwise they might take a drink while spending an idle day in Dingle having sold fish or the like, or during a wedding in Ballyferriter, or at a wake or funeral on the Island. A small amount of alcohol was enough to make them merry.

FIRE AND LIGHT / Tine agus Solas

They burned scraws, or top-sods of turf, when the season's supply of black turf was exhausted. Stumps of heather or charred stalks of heather were used to boost the dying embers, especially after a wet year when the turf was soggy. It was the women who mostly brought home the turf with the donkeys and panniers, and it was also they who carried the bundles of giant heather on their backs. Pieces of driftwood were also burned in the fire, wood which was not suitable for carpentry or any other practical purpose.

LAMPS / Lampaí

Until the end of the 19th Century they had a cresset, called a "slige", for light. It was a metal vessel in the shape of a shell. Formerly the scallop shell was used for the same purpose, which would explain the origin of the word "slige". It was filled with fish oil or extract; a peeled rush was immersed in the vessel with the tip, which was lit, jutting out over the edge of the vessel. Though not very effective, this was for many years their sole source of artificial light.

After that came the paraffin lamp, a tin lamp in the shape of a can, and a pipe on the outside with a wick up through the middle soaked in paraffin – that was their light source up to modern times. The paraffin lamp with glass globe was introduced late, and this was used on the Island and the mainland until the advent of electricity. Electricity never reached the Great Blasket.

SOCIAL ACTIVITIES & RECREATION / Comhluadar agus Caitheamh Aimsire

The village itself was divided into two sections: the lower village and the upper village. There was always a slight edge to the competition between them. They always said that life was nobler in the lower village, and there was some truth in that. Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin lived there, as did Peig Sayers when she married. (In due course Peig moved to one of the new houses in the upper village.) Both Island poets, Seán Ó Duinnshléibhe and Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin (Muiris Ó Súilleabháin's great-grandfather), lived in the lower village. The best musicians and singers lived there: the Súilleabháin family, the Dálaigh family, and the Catháin family. In these noble pursuits the lower orders, so to speak, had the upper hand on their neighbours above!

The village itself was divided into two sections: the lower village and the upper village. There was always a slight edge to the competition between them. They always said that life was nobler in the lower village, and there was some truth in that. Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin lived there, as did Peig Sayers when she married. (In due course Peig moved to one of the new houses in the upper village.) Both Island poets, Seán Ó Duinnshléibhe and Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin (Muiris Ó Súilleabháin's great-grandfather), lived in the lower village. The best musicians and singers lived there: the Súilleabháin family, the Dálaigh family, and the Catháin family. In these noble pursuits the lower orders, so to speak, had the upper hand on their neighbours above!

Even so, the upper village had its own distinctiveness. Pádraig Ó Catháin, the King, lived there. When the famous visitors started to arrive they stayed in the upper village – Synge, Marstrander, Flower, and many others. "Where does that leave all your noble ways now," they would say. "Haven't we got our own poet now, Mícheál, Peig's son".

No mere jibes, but vigorous keen competition to be found in any place which is truly alive.

The "Dáil" or Assembly, as they called Tomás Ó Cearnaigh, the "Yank's" house, was in the upper village. It was there people gathered every night to discuss events, while the young people teased each other. When they had visitors all the fun, dancing, music and singing was in the new houses. Most importantly, the well was in the upper village. The women congregated there during the day, some fetching water, some washing clothes, and others simply talking and gossiping.

On summer evenings they would go back to the top of Tráigh Ghearaí, and dance sets to lilted tunes, and return again to one of the houses in the upper village to round off the merriment. Their lives would change dramatically when the last of the visitors left at the end of summer and the long dark nights set in. Life closed in around them and from then on it was a dreary, depressing time, that is unless you were satisfied with the company of storytellers and their Fenian tales.

MUSIC AND SONG / Ceol is Amhráin

While the mainland depended on the Jews harp or melodeon, they had the fiddle on the Island, and a unique style of playing. It was a soft gentle style that would waken the dead from the grave with its serenity and tenderness. It had an otherworld quality. The Súilleabháin, Catháin and Dálaigh families were the fiddlers. Some musicians managed to craft their own fiddles.

While the mainland depended on the Jews harp or melodeon, they had the fiddle on the Island, and a unique style of playing. It was a soft gentle style that would waken the dead from the grave with its serenity and tenderness. It had an otherworld quality. The Súilleabháin, Catháin and Dálaigh families were the fiddlers. Some musicians managed to craft their own fiddles.

They had a great abundance of songs: Raghadsa is mo Cheaití ag Válcaeireacht (I Will Go Strolling with my Katy), Bá na Scaelaga (Skelligs Bay), Réchnoc Mná Duibhe (The Dark Woman's Smooth Hills), Cailín Deas Crúite na mBó (The Pretty Milkmaid), Beauty Deas an Oileáin (The Fine Beauty of the Island), and the many other songs composed by Seán Ó Duinnshléibhe. They had many more songs, too numerous to mention, and no shortage of singers either. Tomás Ó Criomhthain sang Caisleán Uí Néill, a much-loved song, at his own wedding. They liked to dance a set, or perhaps an eight-hand or four-hand reel, but only a few of the Islanders maintained the tradition of dancing solo.

Spinning, knitting and patching were the main night-time occupations of the women. Young women would have other matters on their mind, no doubt, sporting and playing in the "Dáil", or discreetly courting elsewhere. Nature takes its own course! Men who did not feel like going to the "Dáil" visited other houses where they occupied themselves in discussion and heated debate.

VISITORS AND THEIR INFLUENCE / Cuairteoirí agus a dTionchar

The Islanders had little welcome for visitors until the beginning of the 20th Century. The memory of bailiffs and land agents was still vivid, and the harassment they suffered when the landlords sought rent was still ingrained. It was not at all surprising, therefore, that they would feel unwelcoming when the first famous visitor, J. M. Synge, arrived on the Island in 1905, although we have no other evidence for that except their own displeasure at his account of the visit afterwards which angered a few of them, especially in the King's home where he had stayed and which he never visited again.

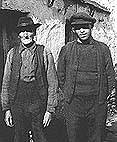

The Norwegian Carl Marstrander was the next famous person to visit there in 1907. They called him "The Viking", apparently with affection, because from the first day he set foot on the Island he worked and laboured both on sea and land with them as one of their own. An Old Irish scholar and a linguist, he went to the Blasket to learn Modern Irish. Marstrander the Viking also stayed in the King's house and he was introduced to Tomás Ó Criomhthain within a short time. Tomás was the "professor" henceforth and Marstrander the pupil.

In many ways, Marstrander was an heroic figure, especially in his physical vigour and mental energy, and because of the way he fitted in with the Islanders he gave them a new perspective on life and instilled in them an esteem for their own culture. It could be said that it was he who kindled the living flame in them. But he left, and afterwards was appointed to teach Old Irish in the School of Celtic Studies in Dublin, where a young scholar from the British Museum came to read Old Irish under his tutelage. That scholar was Robin Flower, and before long the Viking had guided him towards the Blasket, and Tomás was recommended as his "professor". He arrived in 1910 and stayed in the King's house. Flower and Tomás worked diligently together and established a lasting rapport . The whole Island had great affection for Flower, and as a mark of this they called him "Bláithín" (Little Flower). It was "Bláithín, together with another two Englishmen, Seoirse Mac Tomáis, (George Thomson) the great Greek scholar, and Kenneth Jackson, the Celtic scholar, who roused the Blasket community to put pen to paper and write in their own language about their own lives and the people around them, instead of merely writing accounts and snippets of folklore for the publications, An Lóchrann and An Claidheamh Soluis.

In many ways, Marstrander was an heroic figure, especially in his physical vigour and mental energy, and because of the way he fitted in with the Islanders he gave them a new perspective on life and instilled in them an esteem for their own culture. It could be said that it was he who kindled the living flame in them. But he left, and afterwards was appointed to teach Old Irish in the School of Celtic Studies in Dublin, where a young scholar from the British Museum came to read Old Irish under his tutelage. That scholar was Robin Flower, and before long the Viking had guided him towards the Blasket, and Tomás was recommended as his "professor". He arrived in 1910 and stayed in the King's house. Flower and Tomás worked diligently together and established a lasting rapport . The whole Island had great affection for Flower, and as a mark of this they called him "Bláithín" (Little Flower). It was "Bláithín, together with another two Englishmen, Seoirse Mac Tomáis, (George Thomson) the great Greek scholar, and Kenneth Jackson, the Celtic scholar, who roused the Blasket community to put pen to paper and write in their own language about their own lives and the people around them, instead of merely writing accounts and snippets of folklore for the publications, An Lóchrann and An Claidheamh Soluis.

The Irish scholar Máire Ní Chinnéide and the student Léan Ní Chonalláin approached Peig Sayers and persuaded her to write her autobiography for them, although it was Bláithín and Kenneth Jackson who first recognised her talent before that when recording Scéalta ón mBlascaod (Stories from the Blasket) from her. Peig's scribe was her son, Mícheál Ó Gaoithín, to whom she dictated her life story.

The Irish scholar Máire Ní Chinnéide and the student Léan Ní Chonalláin approached Peig Sayers and persuaded her to write her autobiography for them, although it was Bláithín and Kenneth Jackson who first recognised her talent before that when recording Scéalta ón mBlascaod (Stories from the Blasket) from her. Peig's scribe was her son, Mícheál Ó Gaoithín, to whom she dictated her life story.

It was thanks to Seoirse Mac Tomáis that Muiris Ó Súilleabháin completed his autobiography, Fiche Blian ag Fás (Twenty Years A Growing). As it transpired, Muiris had only the one book in him; he wrote a second book about his life as a Garda in Connemara but it has not been published. Of all these famous visitors to the Island, however, it was Brian Ó Ceallaigh from Killarney who reaped the greatest harvest there. "An Seabhac" (Pádraig Ó Siochfhradha) urged him to go there to improve his Irish, and gave him a letter of introduction to Tomás Ó Criomhthain. That was in 1917, and it did not take him long to discover the spark in Tomás, and in order to spur him to action he read some of Pierre Loti's and Maxim Gorky's work to him, as if to suggest that if their sort could write great literature about the simple lives of fishermen and peasants, surely Tomás could do likewise. That was how Tomás's diary Allagar na hInise and his autobiography An tOileánach (The Islandman) came to be written within the space of 10 years.

The first to put pen to paper was Tomás Ó Criomhthain. The Blasket books generated controversy and debate on the Island. Writers were accused of misrepresentation – "that is not how it happened"; "all lies and invention". Much of this criticism was inspired by envy. Behold, however, the result of their collective efforts up to and including our own time. Other less important books were written by Tomás and Peig, and by two of their sons, Seán Ó Criomhthain and Mícheál Ó Gaoithín (Maidhc File). Since then other books have been written by islanders – Seán Sheáin Í Chearnaigh, Máire Ní Ghuithín, Seán Faeilí Ó Catháin, and Seán Pheats Tom Ó Cearnaigh. They are all draining the last drop with melancholic longing for the past, while the Island where they were born and reared is now home to one-night strangers and stragglers – gulls and ravens – who merely pick the bones.

The first to put pen to paper was Tomás Ó Criomhthain. The Blasket books generated controversy and debate on the Island. Writers were accused of misrepresentation – "that is not how it happened"; "all lies and invention". Much of this criticism was inspired by envy. Behold, however, the result of their collective efforts up to and including our own time. Other less important books were written by Tomás and Peig, and by two of their sons, Seán Ó Criomhthain and Mícheál Ó Gaoithín (Maidhc File). Since then other books have been written by islanders – Seán Sheáin Í Chearnaigh, Máire Ní Ghuithín, Seán Faeilí Ó Catháin, and Seán Pheats Tom Ó Cearnaigh. They are all draining the last drop with melancholic longing for the past, while the Island where they were born and reared is now home to one-night strangers and stragglers – gulls and ravens – who merely pick the bones.